Our English word “faith” comes from the Latin fides, meaning “fidelity” or “loyalty,” and in Christian usage it was employed to translate the Hebrew emunah (אמונה) which carried a meaning of security, supportiveness, and firmness.

Faith originally did not mean credulity, believing something simply because someone tells you to believe. It meant being secure in what you know, a meaning closer to “confidence,” although there is an element of non-thinking: emun means “craftsman” in Hebrew, someone who is confident of his ability without having to think about it.

Many Christians derive their conception of faith from the Letter to the Hebrews:

11:1 And faith is confidence in things hoped for, a conviction in matters not seen, 2 the elders were recognized for this; 3 by faith we understand the universe to have been caused by the Word of God, that visible things did not arise from something visible.

Far from justifying blind acceptance of dogma, this definition of faith merely distinguishes the “invisible God” (Letter to the Colossians 1:15) from created things, which we can detect with our senses, and establishes faith as applying specifically to the former. Even so, there is a much richer vision of faith in AUR, giving it an integral meaning in the Christian idiom beyond merely justifying belief in the unseen.

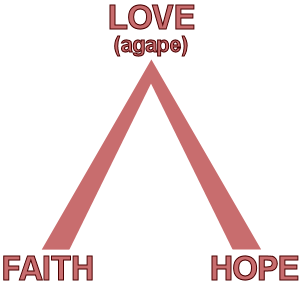

Faith has been described as one of the three “theological virtues” alongside love and hope, and it helps to think of it in relation to the other two.

Love, also called charity, or agape (αγάπη) in Greek, is the greatest of the three theological virtues which also include faith and hope (q.v. the Letter to the Corinthians). Here, love refers not to filial, romantic, or sexual love, but the unconditional love of all of God’s works.

As Jesus teaches, according to the Gospel of Matthew:

5:43 You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ 44 But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, 45 that you may be Children of your Father in heaven. He causes his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous.

46 If you love those who love you, what reward will you get? Are not even the tax collectors doing that? 47 And if you greet only your own people, what are you doing more than others? Do not even pagans do that? 48 Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect.

When Jesus alludes to becoming Children of God in verse 45, this is an echo of the Gospel of John 1:12, wherein we are told that all who accept the Name — another term the ancients used to refer to the Word/Logos, or Son, of God — shall be Children of God as Jesus was Son of God, through whom all things were created and in whom all things are reconciled.

Therefore spiritual love is not love of this or that thing in particular, but love of all things in Creation. And, it is not a vague love of “things in general,” but a love that understands the distinction between your friends and enemies, between the evil and good, the righteous and unrighteous, yet bids you love them all.

All-reconciling love is identified as the key virtue of the Logos, who “sits on the [two] cherubim and holds all things together,” as early Church leader Irenaeus described in his book, The Detection and Overthrow of the So-Called Gnosis. This vision of the Lord is critical to understanding the theological virtues, because it demonstrates the relationship between the three: Love sits atop faith and hope as the Logos sits atop the two cherubim.

The two cherubim here refer to the twin angels on the Ark of the Covenant in Jewish scripture, from between which the spirit of the Lord spoke. Some sources assert that these two cherubim represent the punitive and benevolent aspects of God, which were reconciled in the Lord. Similar pairs are found throughout Abrahamic traditions:

- Two Trees of Paradise: Judgment (Good/Evil) and Life

- Adam, ‘Man’ (אָדָם) who ate of the first Tree; and Jesus, ‘Son of Man’ (בן אדם) as “The Second Adam” who ate of the second Tree

- Law (תּוֹרָה) and Wisdom (חכמה) in Judaism

- Scripture (كتاب) and Wisdom (حكمة) in Islám, Qur’án 2:129

- Lion (or wolf, or leopard) and the Lamb (or kid, or calf) in Isaiah 11:6

- Shrewdness of Serpents and Innocence of Doves in the Gospel of Matthew 10:16

Faith and hope form such a pair, and are also complements which are reconciled in the all-embracing virtue of love.

As God is the God of all of Nature, and not merely the God of humanity or of a particular sectarian institutions, these virtues are better understood in practical terms, rather than epistemological or sectarian terms.

Faith, rather than meaning credulous obedience to dogmatic authority, is simply what we would call “stick-to-it-iveness”: a confidence that is not shaken by contest and competition, or lured away by fleeting temptations. It is the same faith as that found in a “faithful” husband or wife, the same faith in the military oath “to bear true faith and allegiance.” Faith is a virtue in marriage and the military not because one’s spouse is the best partner on Earth or because every battle can be won but because, without faith, the reality supported by that faith crumbles to dust.

Faith is the virtue of focus, of a strong and confident character. Faith is the focus of Law and Judgment, the strength of the Lion and shrewdness of the Serpent.

Hope, on the other hand, is the liberal attitude of a mind that remains open to better circumstances, not obsessing on the negative. When the focus of faith misses the mark, hope renews, opening up opportunities previously unseen. It is the positive attitude that, while it may be proven wrong in epistemological terms, is of inestimable value in practical terms.

Hope is the virtue of open-mindedness, of character innocent of despair, as the Dove and Lamb are innocent. Hope is the Wisdom that knows all things must pass, and that Life (Life with a capital “L,” not my particular life) will go on.

Without faith focusing on the nitty-gritty particulars of judgment and law, hunting like a lion and watching like a serpent, hope becomes mere naïveté. Without hope open to all the wisdom and possibilities of life, remaining as playful as a lamb and light as a dove, faith becomes mere rigidity.

Together, distinguishing the details yet open to all Creation, hope and faith are reconciled as love.