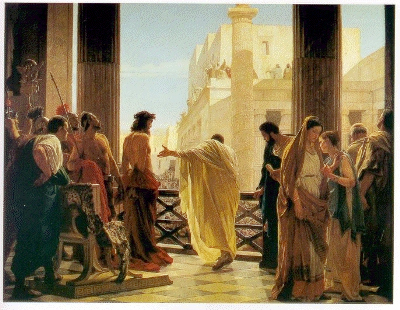

One of the more controversial aspects of traditional Passion plays is the scene wherein Pontius Pilate offers to release one prisoner to the Jews, as part of what the Gospels indicate is a Passover custom in Roman-occupied Judea.

One of the more controversial aspects of traditional Passion plays is the scene wherein Pontius Pilate offers to release one prisoner to the Jews, as part of what the Gospels indicate is a Passover custom in Roman-occupied Judea.

The crowd gathered below chooses the criminal Barabbas, and insist that Jesus be crucified. The scene is often decried as anti-Semitic for its negative portrayal of the Jews as a violent, criminal mob, politically motivated and spiritually blind. Indeed it has often been used to stir up hatred against Jews.

But, a deeper meaning available in this scene is entirely missed by most. It begins with an understanding of the symbolism in the name Barabbas, which is Aramaic for “Son of the Father.” In the context of Christian theology, therefore, those gathered before Pilate chose the man who was named “Son of the Father” rather than the man who was the Son of the Father.

They chose outward appearance over inner reality.

Image v. Substance

Barabbas is identified in the Gospels as a “bandit” or revolutionary who was charged with starting a political uprising. Jesus, shortly before, (in John’s Gospel) made clear to Pilate that his kingdom was “not of this world.”

A more distinct contrast could not be made between the political aggressiveness of nominal “Son of the Father” Barabbas and the spiritual centeredness of genuine “Son of the Father” Jesus, but one slander of the Judean congregation makes this even more clear. In fact, it is how the crowds open their indictment of Jesus before Pilate in Luke’s Gospel: “He opposes the payment of taxes to Caesar.”

Of course, anyone even vaguely familiar with the teachings of Jesus as depicted in the canonical Gospels realizes the absurdity of this. When questioned about the payment of Roman taxes, by those sent to trick him into making revolutionary statements, Jesus asks whose image is on a coin. He is told that it is Caesar’s image. The reply, “render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s, and render unto God what is God’s” is the key to understanding the dichotomy of Barabbas vs. Jesus.

The congregation gathered before Pilate chose the violent and political Barabbas over the thoughtful and spiritual Jesus, and they did so by dismissing Jesus’s actual teachings. Image is chosen over substance, politics chosen over spirituality, and deceit chosen over what Jesus actually taught.

Image-Worship in Christianity

The problem is that the people in today’s world who are choosing the image over substance and scrambling for political power while ignoring the teachings of Jesus are the very Christians who flock to sensational Passion plays, including the infamous Mel Gibson film.

On the Protestant side, they are evangelical disciples of people like John Stott, author of scores of books and the framer of The Lausanne Covenant which is like a constitution for modern evangelical Christianity. According to Stott, the teachings of Jesus are not the important part of the Gospel. The image of Jesus as sacrificing God-man is.

This attitude explains why confessionalism (i.e. swearing allegiance to the group, a political act) trumps introspective moral development in much of the evangelical movement. The crucial thing is that you “love” Jesus, who was God in material form, not that you follow Jesus’s spiritual instructions. According to these sects, those who abide by the moral rules their entire lives, but don’t join the sworn congregation, go to Hell.

On the Catholic side, they are conservatives who wallow in brutal Passion plays like Gibson’s, which gloss over everything Jesus ever told Christians to do, while perversely glamourizing the beating he received in his last days. This is the faction which laments Vatican II and struggles for a return to a Latin Mass few of them can understand, emphasizing the language as if the message were relatively unimportant.

The sound of ancient worldly authority and the image of Christ crucified are paramount. Doing what Christ the spiritual authority advised, before he was crucified? Not so much.

When someone claims to be Christian because they confess that Jesus is the “Son of the Father,” that does not mean they are true followers of the man from Galilee. After all, the Judean congregation before Pilate chose “Son of the Father,” too, but in name only. The real test is whether someone chooses the substance, teaching, and spiritual growth promoted by Jesus over mere images, words, or the power and security of belonging to a congregation.

Afterword : Alternate Interpretation

There are some textual scholars who believe that the Barabbas scene has been corrupted by pro-Roman scribes in order to shift the blame for Jesus’ execution to the Jews. Several early manuscripts actually depict the Jewish crowd calling for the release of “Jesus Bar-abbas,” implying that they were really call for the release of Christ and that the bandit Barabbas was a later invention.

Heaven knows that the Roman faction in the early Church certainly did its fair share of Biblical revision in support of their partisan political goals, so this theory may well be true. After all, they opposed the Desposyni, blood relatives of Jesus, in order to shift the central church (and the flow of church money) from Jerusalem to Rome.

If Jerome of Stridonium can imagine two Marys and perpetual virginity for Jesus’ mother in order to separate Jesus from his siblings, why not invent two Jesus Barabbases in order to separate Jesus from his ethnicity?

If this is, in fact, true then the story of Barabbas takes on an ironic tone. In order to diminish the Unitarian Jews who supported Jesus as the Son of God the Father, Trinitarian revisionists transformed him into a bandit, robbed him of his name, and depicted his Jewish followers as misguided as they would later do to the so-called “Arians.”

Perhaps even, in support of their authoritarian politics, they purposefully counterposed a rebellious Barabbas against the passive Jesus in order to stigmatize rebellion. Food for thought.