On this day in the middle of the 18th century, the “Father of American Unitarianism” Reverend Jonathan Mayhew delivered a sermon on social justice that would later be called “the spark that ignited the American Revolution.”

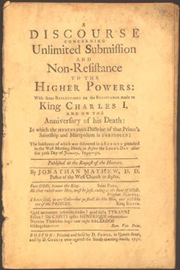

The sermon itself had a rather cumbersome title, A Discourse Concerning Unlimited Submission and Non-Resistance to the Higher Powers, but its message was simple: rulers have the right to reign only so long as their reign is just.

The phrase “submission to higher powers” is a reference to Saint Paul’s Letter to the Romans — a key text used by those who supported the Divine Right of Kings — which contains the language: “Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers, for there is no power but of God: the powers that be are ordained of God.”

Mayhew used rational exegesis to demonstrate that this text could not morally bind people to unlimited submission to an immoral king.

Mayhew’s sermon was called the Spark by John Adams, himself named the “ablest advocate and champion” of American independence by Thomas Jefferson. Of course, Adams might be excused his enthusiasm for Mayhew as a fellow Unitarian Christian, but the critical influence of this single clergyman is undeniable.

Mayhew is also credited with the sermon that started the Stamp Act Riots, and for popularizing the talking point “No Taxation Without Representation” — perhaps America’s first soundbite — which now appears on the license plates of residents of our nation’s capital.

Fighting Rewritten History

&

Debunking Scriptural Arguments

The Spark sermon was even more cumbersomely subtitled With some Reflections on the Resistance made to King Charles I, And on the Anniversary of his Death, In which the Mysterious Doctrine of that Prince’s Saintship and Martyrdom is Unriddled, in reference to the 100-year anniversary of the execution of King Charles.

Many monarchists in Mayhew’s day were hailing Charles as a saint, and calling his execution “martyrdom.” Mayhew’s refutation of this, and of the Divine Right of Kings in general, was a run-away best-seller when published, both in America and Great Britain.

Before Mayhew, foes of the Divine Right of Kings made academic and philosophical arguments against it. However, the doctrine itself was not propped up by academic and philosophical arguments, and thus their assaults resulted in (to use artillery lingo) no effect. Essentially, the intellectual detractors of this tyrannical theory of government were talking past the bulk of the argument and, despite their claims to rationalism, failing to understand the psychology and sociology of rhetoric.

Mayhew’s surgical strike against the scriptural arguments used to insulate immoral government, however, resulted in a political bull’s eye. He didn’t sidestep or denigrate the source of the argument; he analyzed it respectfully and found a different and deeper answer than the superficial exegesis used to prop up systemic oppression.

It is a lesson from the 18th Century that those who seek justice, truth, and freedom in the 21st Century would do well to heed.