Theology Matters

In an age when most believers consider the fine points of theology largely irrelevant to the practical concerns of social and political action, when many would say the only thing that matters in religion is “being a good person,” the questions debated in the earliest centuries of the church about the relationship of God and Christ must seem about as important as how many angels can dance on the head of a pin, particularly to progressive believers.

Trinitarian dogma—the belief that God exists as three co-equal, co-eternal persons with a single substance—goes unexamined in most churches and is no longer questioned even by many who call themselves Unitarian, a term explicitly invented as a direct challenge to the Trinitarian creed.

However, just as the cornerstone sets the plan of a building, our core concept of the nature of reality sets the plan of our world-view. Ideas direct behavior, core ideas most of all. The way we view the ultimate issues of authority, authenticity, morality, justice, and truth echoes thematically throughout the individual psyche and collective culture.

Metaphysics, including theology, matters.

What is Theology About?

When we speak of Unitarianism here, we do not mean the purely nominal Unitarianism of the Unitarian Universalist Association, which no longer promotes any particular theology. We mean theological Unitarianism, the belief that the Creator is one uncreated God, regardless of how many created beings might be called, for whatever reason, “gods.” (See 1st Letter to the Corinthians 8:5-6)

For theological Unitarianism, what you mean when you say “god” makes a difference. The atheist talking point that not believing in the Christian God is just like not believing in Zeus is a semantic fallacy: “god” or not, Zeus is still a created being not at all comparable to the uncreated Source of Existence which is the proper subject of theology. Lumping Zeus and the Creator into the same category, simply because they are both called “god/God,” makes about as much sense as confusing a field mouse with a computer mouse.

Theology is not about the quirks of language—how we use the word “god” or how we arbitrarily label ourselves in associations. Theology is about how we view the ultimate origin and nature of the universe in which we live and act as moral agents.

For theological Unitarians, all substance in the universe has a singular Source which we may or may not call “God.”

Unitarian and Trinitarian

In contrast to Unitarianism, Trinitarian theology speculates that God has a substance, from the Latin substantia : something standing (-stantia) under (sub-) the Divine. This substance is somehow divided up into the three personae of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.

The Latin personae is used to translate the Greek hypostases which, oddly enough, means the same thing as substantia, hypo– meaning “under” and stasis meaning “standing.” So, God has three substances and one substance, but they are mistranslated from one language to the other.

LATIN______________________GREEK

3 personae (“mask”) = ______3 hypostases (“substances”)

1 substantia (“substance”) = .1 ousia (“being”)

Would you like to know how that’s not a contradiction? The Trinitarian answer is that it’s a mystery, so stop thinking about it.

Curiously, the Latin persona (from which we get the word “person”) actually equates to the Greek prosopa, both of which refer to a theatrical mask, which is how the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost were conceived by followers of the Sabellian heresy which was one of the alternate theologies that Trinitarianism was designed to refute!

So, according to Trinitarianism it is heretical to describe God as three masks for one substance unless you insist that when you say “mask” you really mean “substance” and, when you say “substance,” you really mean “being.”

Is your head spinning yet?

The Son persona of God is described by Trinitarian theologians as “begotten” by the Father persona. The Spirit persona is described as “proceeding” from the Father persona and, in some churches, also from the Son persona. But, at the same time, all three personae are described as somehow co-eternal and co-equal with each other.

It is a whirlwind of self-contradiction and bad translation that short circuits reason and can only be propped up by raw authority, a semantic juggling act that relies on the believer’s ignorance of language and philosophy.

For the Unitarian, all substance—all phenomena, all being or existence, including time and space and even the Son of God and Holy Spirit—everything that exists is from God, Who is uniquely beyond under-standing. This Unitarian view subordinates all created things, regardless of status, authority, or even divinity, to an appropriately humble position of fallibility and imperfection in relation to God Most High.

As we shall see, when the infallible, ineffable, and unique God is dragged down into the world of substance and diversity, this allows creatures to be elevated to an inappropriate level of authority and exempted from rational inquiry.

The Originality of Subordinationism

Unitarianism (and the so-called “Arianism” of Christian origins) is often described as denying Christ’s divinity. But this is not an honest description so much as a mere political tactic, similar to the claim that Unitarians “deny the Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit,” which they do not.

A more accurate description of Unitarian Christianity—and the broad range of beliefs in the Early Church that were stamped out by Nicene Christians—would be “subordinationist” because the one belief they all share is that the Father is the One God while the Son and Holy Spirit are subordinate to Him.

Even those subordinationists who refer to the Son as God distinguish the Son’s identity as “God” from “The God” who is the uncreated Father, a grammatical distinction that is made emphatically clear in the original Greek of the first verse of the Gospel of John, but left confused (or simply left out) in most English translations. Although there is no perfect translation in English, this distinction is similar to the difference between saying “the Son is Divine” and saying “the Father is The Divine.”

That definite article makes a difference: the relationship is clearly subordinate and vertical, not coequal, which is exactly what one would expect from a relationship described using Father/Son language. Those who deny subordination are actually the ones who “deny the Father and the Son.”

This subordination is clear not only in a straight reading of the New Testament—a fact punctuated by the sprouting of subordinationist churches like the Unitarians, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Christadelphians whenever a dogma-free reading of the Bible is undertaken—but it was also the position of the early Church fathers.

Saint Justin Martyr (c. 100 – 165), whose works represent the earliest arguments in favor of Christianity, taught that the Son was “another God and Lord, subject to the Maker of all things, who is also called an Angel [i.e., “messenger”] because He announces to men whatsoever the Maker of all things, above whom there is no other God, wishes to announce to them.”

Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 – c. 213) taught that God was uncreated while the Son and Spirit were “first-born powers and first created.”

Irenaeus, writing in the late 100s, described the Son and Spirit as “hands of God” who was the Father.

Origen (c. 185 – c. 250) speaks of the Son as subordinate to God, and as an “image” of the Ineffable as Paul’s Letter to the Colossians (1:15) also asserts. Even though he uses Tertullian’s term “trinity,” he never refers to Son or Holy Spirit as God, and makes clear the subordinate distinction between “unbegotten God the Father” and “His only-begotten Son.”

Subordinationism was the tradition of the Early Church based on the scriptures, a theological tradition which survived the proto-Trinitarian theologies of Tertullian and Sabellius, and culminating in the teachings of St. Lucian of Antioch (born c. 240), Eusebius of Nicomedia who baptized Constantine, and the much-maligned Arius.

Trinitarian theologians are quick to assert that the biblical proof texts of subordinationists have all been refuted, but the refutations are hardly more than baseless assertions themselves, easily-explained back-readings that poorly fit (or even contradict) a plain reading of the texts. The scriptures are so weak in support for Trinitarianism that over the centuries Trinitarian scam artists have injected fraud texts into scripture to justify it, such as the infamous Comma Johanneum which persists in the King James Version despite being universally recognized as a blatant corruption of the Gospel.

In fact, there is a strong consensus among biblical scholars that, of all the various doctrinal discrepancies in our many ancient copies of New Testament scriptures, the discrepancy with the clearest resolution is the one surrounding “adoptionism.”

Adoptionism is a variety of subordinationism that proposes that Jesus was appointed (or “anointed,” the actual English translation of the words Messiah and Christ) as the Son of God. For a variety of reasons, scholars agree that where different texts indicate different attitudes toward adoptionism, the adoptionist reading is most likely the original and the anti-adoptionist reading is a later corruption.

Simply put: Unitarian subordinationism was the original character of the Christian religion, while the conflationist substance theology of Trinitarianism represents a gradual, politicized corruption during the decline of the Roman Empire.

The Origins of Conflationism

Although the term “Nicene” could accurately capture the genealogy of this corruption, the full doctrine of the Trinity was not yet invented at the time fringe bishop Hosius of Córdoba cajoled Emperor Constantine into convening the Council of Nicaea and insisting on consubstantialist language that falsely conflated God the Father with the Son of God.

And yet, the roots of this corruption precede Hosius’s Council of Nicaea by centuries. Biblical scholar Margaret Barker argues that the original Father/Son relationship between El Elyon (God Most High) and Yahweh was covered up by King Josiah, whose followers redacted the Jewish Scriptures that Christians call the Old Testament to reflect their conflationist theology and prop up Josiah’s authoritarian rule. In an ideology where the subordinate Son becomes equal in authority with the Father, the King can similarly rise in authority beyond his proper role as steward of his people.

Barker (who does not dwell on the political implications of the purges and frauds of Josiah) argues that it was the original subordinationist Father/Son tradition which survived among the Jewish people outside of official circles and later gave birth to Christianity, not the authoritarian Josaic conflationism that developed into what we know as Judaism today.

As the original subordinationist faith of the people of Israel began to reassert itself in Christianity, however, authoritarian conflationism was reincarnated with the help of the Greek substance philosophy of the Roman ruling class.

Tertullian, a pagan lawyer in Rome who began calling himself a Christian only in his late 40s, introduced consubstantialism to Christianity and was the first to begin conflating the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost even as he was attacking Sabellians for doing the same thing. Soon, Tertullian dropped all pretense of not being a conflationist when he converted to Montanism, a religion in which the speaker claims to actually be God, the ultimate usurpation of Divine authority.

Tertullian’s weird conflationism persisted despite his apostasy, eventually becoming law when the Nicene Emperor Theodosius issued the authoritarian Edict of Thessalonica outlawing all dissident belief, and convened a Church Council in Constantinople to establish the fully Trinitarian philosophy of the Cappadocian fathers as Imperial orthodoxy.

Since then, objections to Trinitarian dogma have been punished by swift and tyrannical violence. As recently as the turn of the 17th Century in Great Britain, people were executed for questioning the doctrine.

The Authoritarian Function of Conflationism

The term subordinationism might seem to imply a more authoritarian worldview but, ironically, by maintaining a proper chain of transmission, the subordinationist does not usurp an inappropriate degree of authority for himself. When we are but messengers—or in the case of Christians, messengers of The Messenger—we can admit the frailty of our transmission of the message. This even applies in a purely secular idiom: someone who submits to the hierarchy of evidence, expressed natural law, and underlying logical principles is far less likely to exhibit tyrannical tendencies than someone who denies facts, twists logic, and claims to speak absolute, unchallengeable truth.

Those who collapse the hierarchy of authority by conflating its different levels, first by denying the vertical Father/Son relationship and then by asserting perfection for their own transmission of the Message, can claim to speak with the infallibility of the Highest Authority. Conflationism becomes bibliolatry, which becomes autolatry and tyranny.

This sort of hierarchy conflation is echoed in authoritarian thinking throughout history. Ancient despots like the Pharaohs and Caesars conflated themselves with Divinity, but it happens even outside the religious sphere. “L’etat c’est moi” said Napoleon, conflating his individual person with the state. And, Richard Nixon conflated presidential will with the rule of law when he claimed that “it’s not illegal when the president does it.”

While Jesus claimed unity of will with the Father, it was explicitly accomplished through subordinating his personal will to God’s. In the Prayer at Gethsemane, the key moment of Reform Unitarian soteriology, Jesus even hesitated (“take this cup from me”) before full subordination of his will (“nevertheless, Your will be done”). There is no conflation of Jesus with the Father, no co-equal status. If Jesus can be said to “be” God, it is only as the image of God, the same way you can point to a photograph of your father who is not present and say “that’s my Dad,” because the photograph reflects and represents the reality of your father.

Instead of the self-elevation of a Napoleon, this theology is more in tune with Abraham Lincoln’s sentiment, when he said, “My concern is not whether God is on our side; my greatest concern is to be on God’s side, for God is always right.” Subordinationism trumps authoritarianism with a focus on humility, while conflationism tempts us to authoritarianism by collapsing the hierarchy that separating the mere human from the authority of ultimate truth.

Indeed, the chief representative of political authoritarianism in Christian scripture, the Beast of John’s Revelation, conflates himself with God—just like the Montanists that Tertullian joined after injecting the terms “trinity” and “consubstantial” into Christianity.

Maurice Wiles, in his Archetypal Heresy: Arianism Through The Centuries, noted that Trinitarian dogma and political conformism were closely tied, at least among Anglicans. The same can hardly be denied among other Christian denominations, and it is the conflationist elements of Trinitarianism which enable this alliance of Bestial tyranny and religious creed.

Although describing itself as tradition, conflationism is an ongoing corruption masking itself as tradition. Josaic conflationism conflated El and Yahweh, dubiously claiming to have discovered ancient and previously unknown scrolls hidden away in the Temple. Dishonest Christian scribes purged adoptionist verses from their copies of scripture to make it appear as if their conflationist doctrine reached back to the Apostles. The Nicene conflationism propagated by Athanasius claimed to be a tradition resisting so-called “Arian” innovations that had actually been around for centuries independent of Arius. Cappadocian conflationism invented wholly new language in an attempt to reconcile the inconsistencies in previous forms of conflationism.

And, this progressive attack on the hierarchy of authority extends beyond heavenly beings into scripture itself. In the time of Origen, it was known that “as man consists of body and soul (psyche) and spirit (pneuma), so in the same way does Scripture,” referring to the three ways holy writings could be interpreted: materially, psycho-socially, and spiritually. Trinitarians conflated spirit and psyche by official decree in the 9th Century. The “literal interpretation” of fundamentalist churches collapses the traditional hierarchy of interpretation down even further, leaving the mere materialist meaning predominant, all the while claiming to defend the Ol’ Time Religion. Finally, the innovations of plenary inspiration and scriptural sufficiency, both of which are modern reactions against advances in science and textual analysis, conflate the Bible itself with the sublime authority of God.

The end result: any street corner tyrant who can get his hands on a copy of the Bible can claim (as Tertullian did after his apostasy) to speak with the authority of the unbegotten Creator of the entire Universe.

Conflation is not a matter of elevating lower things toward the Prime Mover, but rather consists of dragging God down into the mud. For example, fundamentalists who insist on a materialistic interpretation of Genesis look for evidence of God in particular parts of Creation, as if God were a mere creature and not the Creator for whom everything in Creation is evidence, even the working of natural law that they are so eager to refute. A path that ends in materialism reveals the direction it travels: away from the spiritual and the ultimate truth, and therefore away from genuine authority.

Rather than asking the believer to climb toward God, conflationism aims to let the bibliolatrous preacher drag God down to his level to do his bidding, like some Medieval sorcerer chanting scripture to bind devils.

Mainstream Christianity is practically not Trinitarian

The real problem with the common assertion that Trinitarianism is central to Christian identity is that it simply is not central to Christian daily practice.

Most Christians express their feelings about Christ in a clearly subordinationist way, and rarely if ever have cause to appeal to the absurd and un-Scriptural doctrine of three coequal, consubstantial personae. Even while they may assert that Jesus is “God,” mainstream Christians also see Jesus as praying to and pleading with God, acting as intercessor between man and God, and crying out to God “Why have you forsaken me?”

If the reader will forgive me resorting to personal anecdote for a moment, I was convinced of this fact when a lady who was member of an explicitly and enthusiastically Trinitarian denomination told me that she thought she had once heard the voice of God. When I asked her whether she meant the Father, the Son, or the Holy Spirit, she answered, “The Father, because I’m pretty sure it was God Himself.”

What could “God Himself” possibly indicate, other than a clear understanding—even by a member of a Trinitarian church with no formal training in theology or sophisticated understanding of Christological issues—that the Father is understood to be God in way that is superior to whatever way the Son and the Holy Spirit might be thought of as “God”?

Not only is subordinationism real Christianity, but I would assert that most mainstream Christians are, in practice and underlying faith, not in any way genuinely Trinitarian even today. They may confess Trinitarian creeds in order to satisfy their church leaders, but this absurd theology is not part of how they view God and Jesus, deep down.

God the Father and the Son of God have a vertical, subordinationist relationship in Christian practice that utterly defies theoretical Trinitarian coequality, largely because a plain reading of Christian scripture presents a vertical, subordinationist relationship that defies theoretical Trinitarian coequality. Also, Trinitarian coequality is absurd at face and therefore impossible to intellectually absorb in any meaningful way.

Trinitarian dogma is like an ugly stamp that church leaders have to lick-and-stick all over liturgy and hymnals, to keep reminding parishioners that what they believe in their hearts and read in the Bible is insufficient.

One could abandon Trinitarian theory with hardly a whisper of change in the daily devotions and faith of the average Christian, but the effect on Christian leadership would be considerable. Their distance from Ultimate Authority would expand like an inhaling accordion, and they would lose the ultimate insulation against challenges to their authority: the suspension of reason necessitated by the Trinitarian creed.

A critical function of having an anti-rational core idea is that it gives intellectually-unsophisticated leaders a trump card they can pull out to invalidate the use of reason against their position of power.

While Unitarian minister Jonathan Mayhew (who penned the sermon that hammered the final nail in the divine right of kings) insisted that the clergy have to use reasoned argument to convince their flock, the Trinitarian line is not so diplomatic. You believe that Father and Son are coequal and coeternal because the Cappadocian Fathers said so. You believe that this is in concordance with the Bible, despite that it clearly is not, because if you try to apply logic to the problem you end up in Hell or on the stake. Trinitarian creed is, and always has been, established by brute force and authoritarian fiat.

Subordinationism was the progressive liberating heart of the original Jesus movement, the ancient creative core of Judaism, and the Christian theology of the most active Founders of American liberty and democracy, the ablest opponents of tyranny, who opposed slavery long before it became a Union-shredding crisis, whose premier family in John and Abigail Adams embodied the mutual respect that signifies not only the contemporary best of gender relations—so cherished by the political left—but also the best of marriage and family—so cherished by the political right.

Subordinationist theology, as represented by Unitarianism, matters.

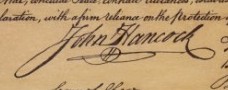

January 12th is John Hancock Day for American Unitarian Reform, the 6th Day of Defiance on the AUR Interval Season liturgical calendar.

January 12th is John Hancock Day for American Unitarian Reform, the 6th Day of Defiance on the AUR Interval Season liturgical calendar.

Today is the First of the 12 Days of Commission, which is the third dozenal of the Easter Season. The 5th Day of Commission, which is the 6th Thursday after Easter, is Agape Thursday.

Today is the First of the 12 Days of Commission, which is the third dozenal of the Easter Season. The 5th Day of Commission, which is the 6th Thursday after Easter, is Agape Thursday. Today is Loyal Thursday, the 4th Thursday after Easter and the Ultimate of the 12 Days of Trust, which is the second dozenal of the Ascension Season.

Today is Loyal Thursday, the 4th Thursday after Easter and the Ultimate of the 12 Days of Trust, which is the second dozenal of the Ascension Season. Today, the second Thursday after Easter, is the beginning of the 12 Days of Blessings, which is the first of the three dozenals of the Ascension Season.

Today, the second Thursday after Easter, is the beginning of the 12 Days of Blessings, which is the first of the three dozenals of the Ascension Season. When it was being decided what to call this movement to reform American Unitarianism, one of the more evocative phrases considered was

When it was being decided what to call this movement to reform American Unitarianism, one of the more evocative phrases considered was